Die Programmatik der Verteilung

Zu sehen ist ein tischförmiges Objekt mit einem rotierenden vertikalen Stab, welcher Garne aus mehreren Richtungen aufspult. Das Tempo bleibt konstant, beharrlich ruhig, die Ressourcen verdichten sich. Sie ballen und konzentrieren sich auf ein Zentrum, den Stab. Emsig arbeiten die verteilten Kone diesem, ihrem gelenkten Ziel zu. Zurück bleibt ein schwerer, behäbiger Riesenkon. Gefräßg hat er sich beleibt, im ständigem Wandel einer wunderbaren Farbigkeit.

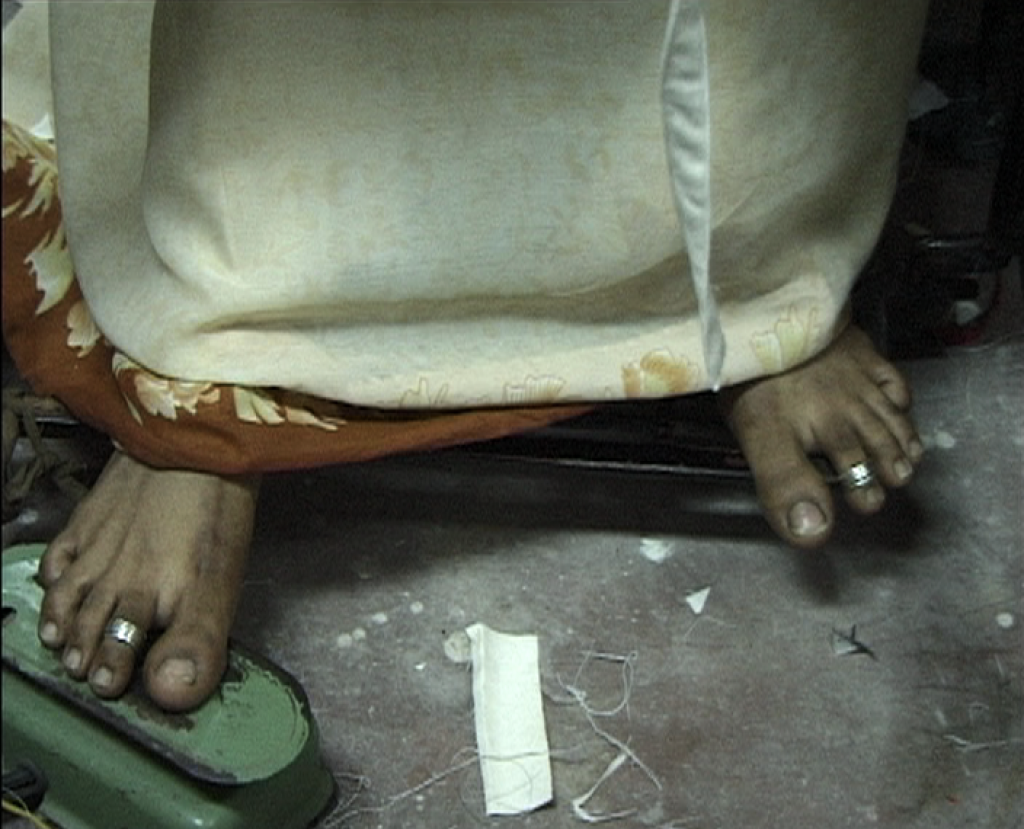

Das Objekt entwickelte sich nach einer Recherche in Indien im Jahr 2004. Dabei galt das Hauptinteresse dem code of conduct. Befragt wurden Textilarbeiterinnen quer durch den Kontinent. Zusammen mit der Frauensolidarität und einigen Politkerninnen versuchte man den dortigen Arbeitsbedingungen nachzuspüren.

Diese Erfahrungen setzten PRINZpod in den filmischen Dokumentationen made in Dignity und globe (Kurzfilm), sowie in mehreren Objekten/Installationen um. Gezeigt wurde die Schau in jeweils abgewandelter Form im ega und Soho Ottakring (Wien), in der Galerie Ute Parduhn (Düsseldorf) und im Großformat in der Werkschau Fadenbrand im Ok Zentrum für Gegewartskunst (Linz).

PRINZpod

2014

Transkript Indien

PRINZGAU/podgorschek

01:01:12.12

Women’s Solidarity has been concerned with women workers’ rights and conditions as part of the Clean Cloth Campaign for many years. The Clean Cloth Campaign has been trying to make consumers in Europe aware of the bad working conditions in the textile industry in the outsourced factories in the south. Critical consumers and workers’ rights activists protested against the companies, who then reacted by devising codes of conduct which appeased the consumers. But we suspected that these codes were merely an image thing .This suspicion was reinforced by the fact that the companies said, “We have this code, we’re doing all this, but we won’t let anyone check up on us.” This special project, the reason for our trip to India, aimed at delving into the matter with the simple question: “Have the Codes of Conduct really helped the women concerned?”

01:02.31:04

01:04:04:05

STEP is a Swiss foundation who awards a seal of approval within the carpet industry. In Delhi, we met the Indian coordinator of STEP, Manshu Gupta, who explained in detail how STEP works and the next day we had the chance to visit a carpet manufacturer in Jaipur. It was a family business and they showed us everything. We got the impression they treated their women workers very well, but did consider that this was owing to the family’s goodwill, not due to any monitoring or regulatory process. The company, Marudhar Exports, had had talks with STEP, but was insufficiently informed about the criteria it had to fulfil, and for Marudhar Exports it was perhaps just a way of selling their carpets.

01:08:29:22

In Tirupur in Coimbatore District, we talked to women textile workers from different factories. They were kind enough to agree to meet us in the small village school after their very long working day. 1:08:54:06

01:10:22:00

These women told us about their working conditions. The main grievance was the extremely long working hours, and the question they posed to us was: “Why do people in Europe and the USA buy so much before Christmas? We can hardly cope with the workload at such times.” The other problem they mentioned was that pregnant women stopped coming to work, because they were harassed so much that it endangered their health and the unborn child.

01:24:49

A big problem in connection with the textile industry is the water supply. In the surrounding rural areas of these textile centres, agriculture is increasingly suffering because the textile industry uses so much water for production. The working conditions in the textile industry are very hard, and at the very bottom of the social ladder are the workers in the dye-works. Dye-works get their orders from the textile factories and must respond immediately and set to work at any time of day or night. The factory says, “We need a certain number of bales of red cloth.” So the workers have to be on standby all the time. This kind of work is mainly done by dalits, and they get by far the least wages, risk their health the most, because of the toxins used in the bleaching and dye works, and get no social security. 01:26:13:18

01:30:51:03

One thing we definitely realized from this trip to India is that codes are hardly relevant in a country such as India. In India 95 % of the work is informal work without a contract. A Code of Conduct might be an instrument for the formal sector, but the informal work sector requires entirely different measures. Codes of Conduct are useful for NGOs in that they help to raise the issue of workers’ rights and women workers. It is a basis for discussion between women workers and employers. In that respect they can be used as an instrument for creating awareness. I believe it is more important to support the work of the unions, to help the women to organise themselves, because one of the key issues to understand is: No one can represent and fight for women workers’ rights better than the women workers themselves. 01:32:17:22